On various pages of this website, sugar forms/moulds/cones and collecting jars/pots are mentioned but nowhere is there an explanation of them.

Used by the earliest refiners through to the late 19th century (in UK) to produce sugar loaves, the moulds were necessary to hold the hot sugar as it crystalised, drained and cooled, whilst the jars collected the molasses and syrup that drained from the sugar ... the moulds sat in the jars.

The shapes of both were determined by the process and designed specifically for the process. There was little variation over many centuries.

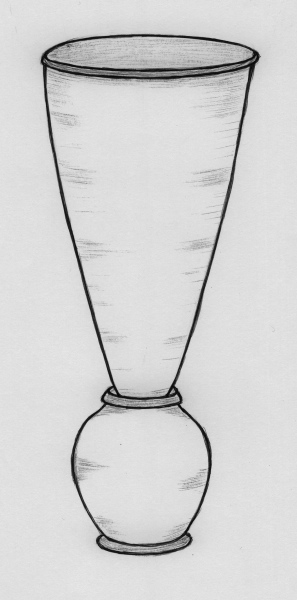

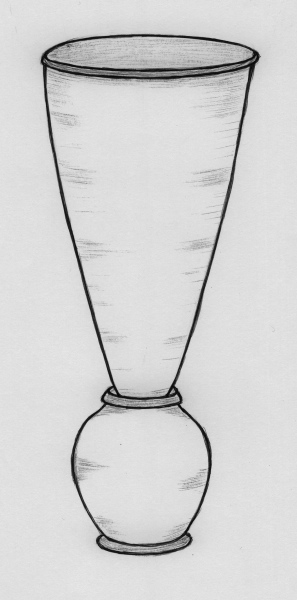

|

< ... thickened rim that took most of the knocks during use. (17" diameter)

< ... thin-walled mould, smoothed or slipped internally. (28" high)

< ... the taper not only assisted the release of the sugar loaf, but also directed the flow

of molasses and syrup to the 1" diameter hole from which it dripped into the jar below.

< ... heavy rolled rim, tapered on the inside to accept the mould. (4" inside diameter)

< ... thick-walled jar to take weight of mould and sugar. (9" diameter, 13" high)

< ... heavy foot. (7½" diameter)

|

| York sugar loaf mould and collecting jar - after Brooks, 1983. |

The example above would probably have been the largest used at the small York sugarhouse (1676-1709), thus producing the poorest quality sugar. The smallest found, for best quality sugar, were only half the size.

In the UK the variations were small ... the thickness and shape of the rim of both items, of the foot of the jar and of the small hole in the mould. Perhaps there was more variation with time, as there's evidence (Jarrett) that moulds were internally slipped from around 1700, and (Sales) of iron moulds being used in the 19th century.

I think also that there were local variations early on ... the small moulds (Liverpool) made by a local potter appear less conical.

In France (Du Monceau), moulds were much the same, however one style of jar had five feet extending down from the body rather than the ring foot.

|

| Museum of Liverpool, 2012.

Fragments of moulds from excavation of Manchester Dock, 2007.

Five mould fragments.

To left, part of a large mould in red clay, unglazed, ½" body, drain hole 1" diameter with a thickened rim.

To right, a small mould almost complete, ¼+" body, approx 7" diameter and 17" tall, drain hole ¼" diameter.

|

|

|

| Museum of Liverpool, 2012.

Fragments of jars from excavation of Manchester Dock, 2007.

To rear, lower part of large collecting jar, 7" base, course fabric ⅝-¾" thick, glazed inside.

Front right, rim of different jar, 3½" inside rim diameter.

The flatish piece front left (also in first picture) is the upper part of a large mould produced locally by Ashcroft of Prescot.

(For Prescot, see below.)

* Fragments found in the infill behind the dock walls.

|

|

|

| |

images © Bryan Mawer, 2012,

with permission of National Museums Liverpool.

|

The moulds only just sat in the jars, a few inches maybe, for the jars were required to catch the run-off from the mould and take their weight, not balance them vertically - that was the job of the neighbouring moulds.

Such sugarhouse pottery had to be extremely hardwearing. Tielhen's 1760 production regime, and Du Monceau's sketches from almost the same time, show that the moulds had a hard life. About every two weeks they were ...

washed,

stacked, point up,

carried or rolled, in their stacks, to the fill house,

the small hole filled with rag,

arranged, point down, in massed ranks, either simply supporting each other or with moulds, point up, in between,

filled with hot sugar to a couple of inches from the top and stirred for even crystalisation,

allowed to cool for about three days,

hoisted through 'pulley holes' to top floor of building,

rag removed from holes,

again arranged in massed ranks, this time with each mould sitting in a collecting jar,

tops trimmed and a syrup or clay solution added to drain through loaves to remove colour - often more than once,

stand for up to ten days to lose colour and harden,

with a number of thumps to sides, loaves knocked out,

loaves away to be finished and baked,

moulds back down through 'pulley holes' to be washed again ... and again ...

Entries for the very early sugarhouse in Ipswich (1617-1621) show that the forms (moulds) and pots (jars) came from Stoke [Ipswich?, or maybe Stocke, Essex?], and a common repair/strengthening was performed locally on the larger moulds ...

|

Paid unto Peter Wilbart the pot maker

for forms and pots made in Stoke from July

1618 until the 2nd January the which was the time he did account

and did amount unto the sum of £37.12s.2½d

... and six months later ...

Paid to Robert Wilson cooper the 18 day of January

1618 for small hoops and great hoops set upon the great

forms at the [ ] together as by a bill from Robert

Debedge and the coopers mark to the receipt the sum of 17s.6d

this should have been before the rate

|

Prescot, Liverpool, 1754 (from Angerstein) É

ÓIn the pottery making the sugar moulds, the furnace is built in the same way as mentioned, but no Chapsels were used for the firing of the larger-size earthenware vessels. The brownish red clay is used for this purpose and is well mixed and kneaded but it is neither dispersed in water nor sieved through hair cloth. During the throwing of the large vessels a boy is also employed to furnish the motive power by winding a crank. A sugar mould, 2 feet 3 inches in height and with a capacity of 10 gallons, sells for 7 pence. A smaller one, 1 foot 6 inches in height and 9 inches in diameter at the large end, is sold for 3 pence and one of 1 foot 3 inches in height for 2½ pence. There are workers who put hoops of hazel round them as soon as they come out of the kiln. They are paid separately and get 3 pence per dozen.

Moulds for sugar Candy are made on the same way, but are closed at the top and have small holes at the sides. They are sold at the same price as the sugar moulds.Ó

... & SUGAR LOAVES

|

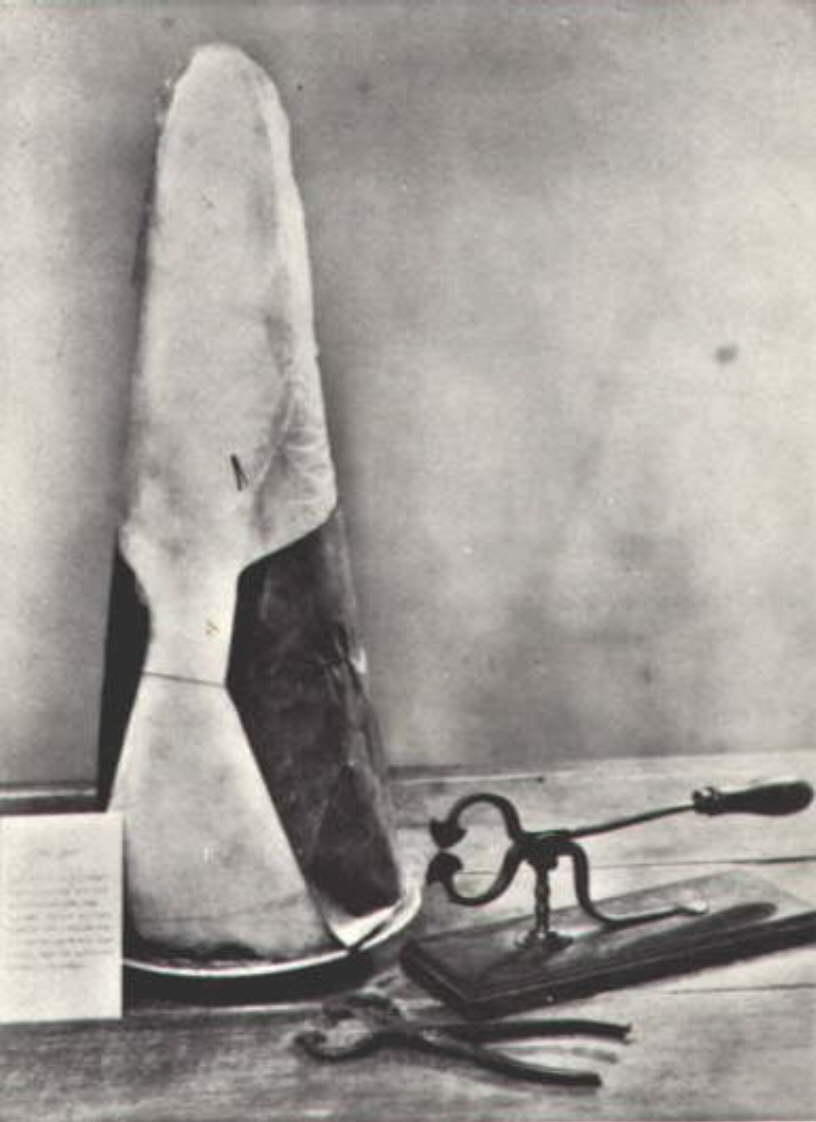

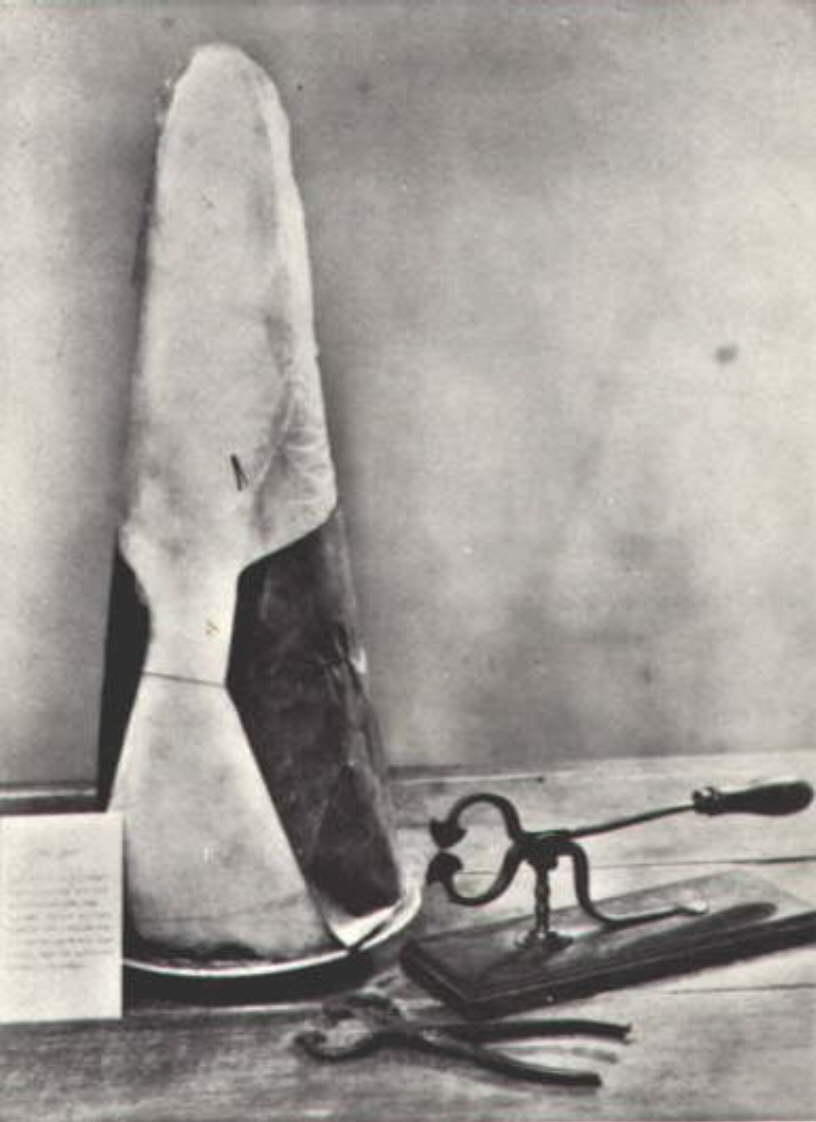

Once drained and firm, and knocked out of the moulds, the loaves were baked in the huge refinery stoves at 140ûF. When cool, the molasses-rich tips were removed and the loaves reshaped.

Wrapped in blue paper (patented 1666) to enhance the whiteness, they went on sale in various sizes from maybe 8" to 28" ... the smaller the loaf, the higher the quality and the price.

Also sold in part loaves as 'lumps', 'pieces' and 'ground', loaves were cut into usable pieces using sugar nips.

|

19C Sugar Loaf and Nips,

with permission of Cambridge & County Folk Museum. |

Sources ...

For accurate, detailed profiles of moulds & jars ...

Brooks - Post-Medieval Archaeology, Vol 17, 1983, pp1-14. "Aspects of the sugar-refining industry from the 16th to the 19th century" by Catherine M Brooks.

Jarrett - Post-Medieval Archaeology, Vol 38/1, 2004, pp17-132. "Excavations at Deptford on the site of the East India Company ... , London" by David Divers.

For illustrated refining process in 18th century sugarhouse ...

Du Monceau - "Art de Rafiner le Sucre", by Duhamel du Monceau (1764), Connaissance et Memoires Europeennes, 2000.

For real-life examples of moulds & jars ...

Liverpool - Museum of Liverpool, display regarding Manchester Dock (2012).

For Prescot Pottery É

R R Angerstein's Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753-5 - Industry in England and Wales from a Swedish Perspective, translated by Torsten & Peter Berg, 2001.

References to this website ...

Sales

Tielhen

Ipswich

... and Archaeology